|

Worship

in The Salvation Army

by Major Harold Hill

Lex orandi, lex

credendi

Attrib. Prosper of Aquitaine (5th century)

The law

of prayer is the law of belief, or, as we pray, so we believe.

It was long held that Salvationists, in good Wesleyan

tradition, imbibed their doctrine from their Song Books. Even

the reflection that most Salvationists today would more likely

learn their catechism from the Data Projector continues to

impress on us the significance of what takes place in public

meetings. The theology inculcated may however have changed

somewhat over the years. For the purposes of this exercise, by

“worship” we mean what groups of Salvationists do when

gathered for religious meetings.

We can

distinguish three very general periods or phases in Salvation

Army worship style, roughly parallel to the sociologists’

analysis of Salvation Army history – not sharply defined of

course but overlapping and varying according to locality and

cultural differences.

1.

1865 – c. 1900: The Phase of Enthusiasm

Early

“private” gatherings of the Christian Mission – “cottage

meetings” in private homes or conference-type gatherings in

larger venues – were not extensively written about, though the

pages of the Christian

Mission Magazine might yield some indications. The

participants perhaps felt no need to describe them and

outsiders were not interested. We may surmise that they

consisted of the usual non-conformist hymn sandwich of prayer,

singing, reading and exhortation. The “Ordinances of the

Methodist New Connexion”, to which William Booth would have

been accustomed, provided for the following:

In the

Sabbath Services the following order is usually observed: a

hymn – prayer – a chant, when approved – reading the

Scriptures – a second hymn – the sermon – another hymn – the

concluding prayer and benediction.[1]

The

Christian Missioners’ exercises would, in addition, have

included testimony, monthly celebrations of the Lord’s Supper,

and Love Feasts – the latter sometimes on the same occasion.

They not uncommonly climaxed in an altar-call; an appeal for

greater consecration on the part of those present, evidenced

by an outward response. The concluding exercise of the 1878

“War Congress”, an all-night of prayer, was described as

follows:

The

great object of the meeting was to address God, and it was in

prayer and in receiving answers that the meeting was above all

distinguished. Round the table in the great central square

[concluded the report] Satan was fought and conquered, as it

were visibly, by scores.

Evangelists came there, burdened with the consciousness of

past failings and unfaithfulnesses, and were so filled with

the power of God that they literally danced for joy. Brethren

and sisters, who had hesitated to yield themselves to go forth

anywhere to preach Jesus, came and were set free from every

doubt and fear, and numbers, whose peculiar besetments and

difficulties God alone could read, came and washed and made

them white in the blood of the Lamb.[2]

However, most of the Mission’s early

gatherings were “public”, and not for worship but for witness.

The main focus of their activity was directed outwards and

deliberately avoided the conventional and churchly. This

activity began in the open air, in the streets, and was

adapted to the class of people they were attempting to reach –

the lower working class and what Karl Marx called the

“lumpenproletariat” or those the sociologists term the

“residuum” (a

class of society that is unemployed and without privileges or

opportunities) in the first

instance. What they did had to grab and hold the attention of

the passers-by, which meant there had to be great variety,

spontaneity, inventiveness, brevity and immediacy and

relevance to the people. This meant extempore prayer, singing

to popular tunes and numerous and brief testimonies,

given as much as possible by people of the same type as they

were wanting to attract; preferably those previously known as

notorious public sinners, drunkards and ne’er-do-wells, but

now miraculously changed. Such people were advertised by their

nom-de-guerre – the “saved railway guard” or the “converted

sweep” or even the “Hallelujah doctor”, Dr Reid Morrison, aka

the “Christian Mission Giant”. Any reading or speaking had to

be short and punchy.

Preaching would always be “for a decision”; to bring the

hearer to a point of repentance or commitment or faith, and to

express that by an outward response by coming forward and

kneeling in front of the congregation. To that extent, the

Mercy Seat (or the drum placed on its side in the Open Air

meeting) would have a sacramental role, providing the locus

for the outward expression of an inward grace. Although this

chapter is not the place for an examination of the principles

which inform “worship” in general, it is worth-while bearing

in mind that one element in all kinds of religious worship is

an attempt to recreate the original theophany, the “God

moment” lying at the heart of a particular faith. So, for

example, the Eucharist is intentionally a re-enactment, an

anamnesis of the “Last Supper” of Jesus with his disciples, or

the Temple ritual with loud trumpets and cymbals and clouds of

incense was thought to recreate the scene at the giving of the

Torah on Mount Sinai, or the glossolalia of a Pentecostal

meeting “singing in the Spirit” might recapitulate in some way

the experience of Acts Chapter Two. Does the repeated call to

the Mercy Seat or Holiness Table in the “appeal” at the

conclusion of a Salvation Army meeting likewise give an

opportunity for Salvationists to re-live their moments of

conversion, consecration and experience of the work of the

Holy Spirit? Is the test of such a meeting the degree to which

this might be said to have happened?

When,

after 1879, brass bands made their appearance, they were

firstly for attracting attention, and secondly for drowning

out the noise made by the opposition, as well as for helping

to carry the singing of hymns and songs. They had the immense

advantage of being in the popular working-class musical idiom.

Folk-doggerel words were set to popular tunes.

All

these characteristics were carried inside, whether they were

inside a theatre or music hall or a bricked up railway arch or

the loft over a butcher’s shop. The style was modelled on the

contemporary music hall, the primary place of entertainment

for the lower classes. A master of ceremonies introduced a

succession of short acts; speech and music alternated.

Salvationists also accepted opportunities to appear as acts in

genuine music hall shows – Bramwell Booth wrote of appearing

on stage as “Item No. 12” at a theatre in Plymouth.[3]

We do

not have many descriptions of how such meetings ran, but some

from the Christian Mission period were recorded. Sandall says:

The

Revival

printed at this time [1868] a long description of a Sunday

afternoon testimony meeting (“free-and-easy”) in the East

London Theatre, contributed by Gawin Kirkham, Secretary of the

Open-air Mission. The testimonies were reported in detail:

The

meeting commenced at three and lasted one hour and a half.

During this period forty-three persons gave their experience,

parts of eight hymns were sung, and prayer was offered by four

persons.

Among

those who testified was:

One of

Mr. Booth’s helpers, a genuine Yorkshireman named Dinialine,

with a strong voice and a hearty manner. Testimonies were

given at this meeting by “all sorts and conditions” and many

were stories in brief of remarkable conversions. The report

concluded:

Mr.

Booth led the singing by commencing the hymns without even

giving them out. But the moment he began, the bulk of the

people joined heartily in them. Only one or two verses of each

hymn were sung as a rule. Most of them are found in his own

admirably compiled hymn book… A little boy, one of Mr. Booth’s

sons, gave a simple and good testimony.[4]

The Nonconformist

described a Sunday evening at the Effingham Theatre in the

same period:

The

labouring people and the roughs have it – much to their

satisfaction – all to themselves. It is astonishing how quiet

they are.

There is

no one except a stray official to keep order; yet there are

nearly two thousand persons belonging to the lowest and least

educated classes behaving in a manner which would reflect the

highest credit upon the most respectable congregation that

ever attended a regular place of worship.

“There

is a better world, they say” was sung with intensity and

vigour . . . everybody seemed to be joining in the singing.

The lines

“We may

be cleansed from every stain,

We may

be crowned with bliss again,

And in

that land of pleasure reign!”

were

reached with a vigour almost pathetic in the emphasis bestowed

upon them. As they reluctantly resumed their seats a happier

expression seemed to light up the broad area of pale and

careworn features, which were turned with urgent, longing gaze

towards the preacher.

Mr.

Booth employed very simple language in his comments …

frequently repeated the same sentence several times as if he

was afraid his hearers would forget. It was curious to note

the intense, almost painful degree of eagerness with which

every sentence of the speaker was listened to. The crowd

seemed fearful of losing even a word.

It was a

wonderful influence, that possessed by the preacher over his

hearers. Very unconventional in style, no doubt . . . but it

did enable him to reach the hearts of hundreds of those for

whom prison and the convicts’ settlement have no terrors, of

whom even the police stand in fear. . . . The preacher has to

do with rough and ready minds upon which subtleties and

refined discourse would be lost. . . . He implored them,

first, to leave their sins, second, to leave them at once,

that night, and third, to come to Christ. Not a word was

uttered by him that could be misconstrued; not a doctrine was

propounded that was beyond the comprehension of those to whom

it was addressed.

There

was no sign of impatience during the sermon. There was too

much dramatic action, too much anecdotal matter to admit of

its being considered dull, and when it terminated scarcely a

person left his seat, indeed some appeared, to consider it too

short, although the discourse had occupied fully an hour in

its delivery.[5]

Clearly,

William Booth was not himself restricted by the rule that any

speaking should be brief, but then again most Victorian

sermons were likely to be of this length or even greater.

What

grew up by trial and error as the most practical way to

proceed became in due course the standard as prescribed by

regulation. The first

Orders and Regulations (1878), largely drafted by Railton,

directed as follows:

Be sure

to keep up from the first that perfect ease and freedom as to

the form of service which always belongs to us.

Drive

out of the place within the first five minutes the notion that

there is to be anything like an ordinary religious service. A

few free and hearty remarks to your helpers, or to persons

just entering the building, whom you wish to come forward,

such as a loud “God

bless you, brother; I’m glad to see you,” will answer this

purpose, astound Christians, and make all the common people

feel at home as much as when they enter the same place amidst

the laughter and cheers of weekdays.[6]

The

Orders and Regulations

also provided a description of the meetings and activities of

the Corps as they would appear to a stranger arriving in the

town, thereby providing the officer with a template. Extracts

convey the flavour:

14.

About a quarter to eight he would observe a procession

marching along, which as it passed would be joined by several

companies.

15. On

nearing the hall he would see another procession of equal size

approaching from the opposite direction, and both would meet

in the presence of a huge mob at the doors.

16. Two

strong men would be seen keeping the entrance with smiling

faces; but with the most resolute silent determination to keep

back the turbulent, and welcome only the well-intentioned.

17. Upon

the front he would observe very large placards, “The Salvation

Barracks” being prominent above all.

18. The

building would be entered through large gates into a yard, and

would turn out to be a plain white-washed room on the ground

floor, capable of seating—on low unbacked benches—some

thousand people.

19. Upon

entering he would find a large number of men present, many of

them of a very low description, and a general buzz of

conversation prevalent. He would be received at the door by a

man who would smilingly show him to a seat. Another would

offer him a songbook for ld.

20. At

one side of the place he would notice a platform, some two

feet high, capable of seating from 50 to 100 people.

21. He

would notice the men as they came in from the open air

disperse, some sitting at the end of forms, some in seats at

the front, and some on the platform.

22. He

would hear one standing at the front of the platform call out

a number, and upon this, order would generally prevail. But

some young men at one side would laugh and make remarks to one

another.

The

leader turning upon them, would caution them to be quiet. One

of them would reply in a saucy manner—another would laugh

aloud.

They

would then be told they must leave the place, and the first

verse of a hymn not given would be started. One of the men

seated at the end of a form near would then request these two

to go out, and upon their refusal would turn towards a man at

the door, who would at once come up with three others and the

two would be dragged out before the end of the chorus several

times repeated. As they were pushed out two of the men would

remain at the door to assist in keeping them out, if

necessary.

23. The

second verse would be given out with an extraordinary remark,

and the singing would be of the loudest and wildest

description, the chorus repeated many times, but always led

off by the leader.

In the

course of singing the next verse many shouts would be heard,

and some would stand on forms and wave their arms.

24.

After this, all would suddenly kneel down and at once there

would be a burst of prayer from one after another, till in a

few minutes six or eight had prayed.

25.

Another hymn would then be at once struck up by the leader,

and whilst it was being sung a very large number of persons

kept outside during prayer would stream into the room, making

it nearly full…

26. The

leader would then announce an extraordinary list of speakers,

and strike up a verse while they came forward. Each speaker

would occupy a few minutes only, eight or nine being heard in

the hour.

27. A

lad would sing a solo between two of the speeches, and one

speaker would announce, amidst many shouts, that he had never

spoken before, but meant to do so again.

28. An

old woman rising near the front would ask for a word, would be

welcomed by the leader, and would then speak in such a way as

to move all present to tears.

29.

Encouraged by this, a big man, wearing rather flash clothes,

would rise and ask a word, but would be informed there was not

time tonight by the leader, who would instantly strike up a

verse.

30.

About the middle of the hour notices of the services of Sunday

and Monday would be given out, and everyone urged to buy and

read on Sunday some publications, to be had at the door.

31. The

leader would then speak after the rest, urging everyone

unconverted at once to come forward and seek Christ, and would

then call for silent prayer, after a minute or two of which,

prayer aloud would begin.

32. The

stranger would now rise to leave; but would at once be spoken

to by someone who would walk towards the door with him, urging

him not to go. He would notice facing him near the door a

motto of the most terrible description, others being placed on

each wall and along the front of the platform…[7]

That was

Saturday night – the hypothetical visitor returned and got

saved on Sunday.

This

prescription is not unlike the description of the Christian

Mission meeting of ten or so years earlier, except that huge

crowds are envisaged and provided for, and an immense amount

of organisation assumed. In some places, that was what it was

like. And when Booth insisted that people “do mission work on

mission lines, or move off”, this is what he meant.[8]

A reporter from The Secular Review attended an Army

meeting at the People’s Hall, Whitechapel in 1879. A selection

of quotes from his article gives an impression of the people

and practices of the early Army:

The congregation is evidently drawn from the poorer classes,

with here and there a young man or woman who may be slightly

superior in point of what the world calls respectability...

These Salvationists are in earnest - plain, vulgar, downright,

most unfashionably earnest...

The service begins with a hymn sung to the air of ‘Ye banks

and braes o’ bonnie Doon’. As the hymn proceeds and the

oft-repeated chorus gathers strength, arms and hands are

raised to beat time with the singing...

And now comes a prayer... and we are compelled to acknowledge

that it is an able one. It moves the hearers’ sympathy. Its

eucharistic cries arouse... cries of ‘Amen!’, ‘Glory!’,

‘Hallelujah!’ from all around.

As for the preacher, Peter Keen, the reporter noted, “He is

natural, and undoubtedly is firmly convinced of the truth of

the gospel which he declares. With a rude, untutored, but

withal moving eloquence, he preaches a sermon upon the

inability of man to do aught for himself, and the consequent

necessity of ‘throwing it all upon Jesus’...”[9]

The 1881

Doctrines and

Discipline of The Salvation Army urged lively and

attractive meetings:

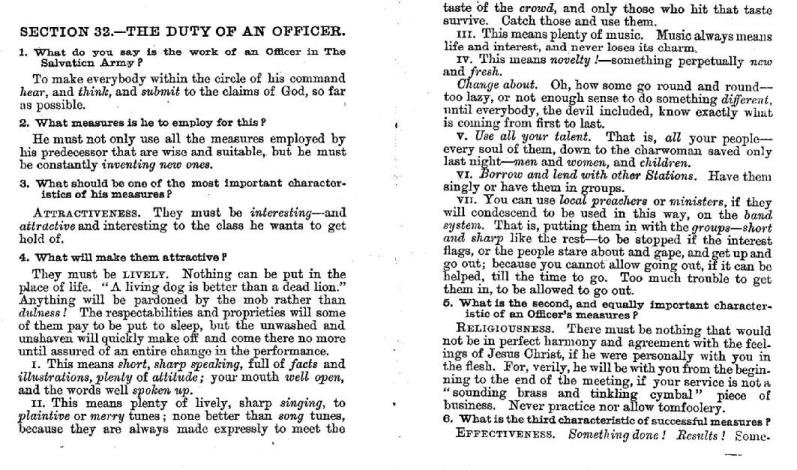

[10] [10]

Various

types of Meetings were prescribed. Apart from prayer meetings

(Knee-drill) there were open-air meetings at various times of

the day, the main purpose of which, apart from bearing witness

and challenging people to be converted on the spot, was to

persuade the public to follow the Salvationist back to their

Barracks for the in-door meeting. There were generally public

indoor gatherings in the afternoon and evening on Sundays, and

on every night of the week.

At first

it was not usual to have indoor meetings on Sunday mornings.

These were the time the working class idled about in the

streets, drinking and gossiping and wasting their free time.

Therefore, non-stop open-air meetings were to be conducted at

this time. Later, when morning indoor meetings came to be

held, these were at first attended by small numbers, usually

only Salvationists, and used for teaching, especially about

Holiness. However, it was not expected that all Salvationist

would attend, because the soldiers, in their brigades or

companies, would take turns away from their own inside meeting

to work in the open air.

The

“Holiness Meeting” was at first usually a week night event,

for soldiers only, with strictly controlled admission by token

or pass. The style would be more restrained, there being no

need to entertain the masses; those attending were there

because they were serious about their religion. Singing,

praying and testifying to “the Blessing” would precede the

sermon. Later, the Sunday morning meeting became known as the

Holiness Meeting and was attended mainly by Salvationists.

There was always a challenge to seek the Blessing of Holiness,

and an invitation to come forward to pray for this.

The

outline of the meeting for the “saints” was therefore the same

as that for “sinners”: all was focussed towards the

climacteric appeal. This might be contrasted, for example,

with the Anglican liturgy where a general confession and

absolution fairly early in the order of events relieves the

worshippers of any burden of guilt and sets them free to enjoy

the rest of the service. In the Army’s meeting plan, any guilt

is relentlessly pursued – sung, prayed and preached towards

the appeal, heightening the participant’s anxiety in order to

ensure their capitulation at the end. Those not making the cut

may take their guilt home with them to ensure their return.

On the

Sunday afternoon there was a “free-and-easy” meeting, like a

music hall concert. Both soldiers and the public attended, and

the opportunity to preach and testify was not neglected. There

was always a challenge to conversion. There was a

church fashion for PSA – “Pleasant Sunday Afternoons” – at

this time, but they tended to be lecture-based. The Army’s

were different, and more focussed.

At night was the “Salvation

Meeting”, when the largest numbers of the public would attend,

and all the stops would be pulled out in the battle for

converts.

The

arrangement of the Barracks followed the lay-out of the music

hall and such places, with a stage for the performers. As the

number of soldiers grew, and the Army built or bought its own

halls, the platform was often tiered; the soldiers sat on the

tiers and the public gathered in the body of the Hall. Only

later, as the crowds thinned towards the end of the century,

did the soldiers start to fill up the hall itself, and the

musicians come to occupy the stage. Booth was insistent that

the musicians were there for support purposes, not to be seen

or heard for their own sake. He was very reluctant to have

singing groups as such – his experience as a Methodist

minister had left him believing “choirs to be possessed of

three devils: the quarrelling devil, the dressing devil and

the courting devil.”[11]

It was some years before “Songster Brigades” were tolerated.

Booth preferred the “Singing, Speaking and Praying” Brigades

initiated by his son Herbert, the members being equally

willing and able for any of those assignments.

While

Booth’s prescription in the

Orders and Regulations

suggests and assumes a very tightly controlled and directed

performance, all under the orders of one person, in practice

the early Army’s spontaneity was at odds with this picture,

owing more to the revivalist camp-meeting. Lillian Taiz quotes

the memoirs of Salvationist James Price:

One

Saturday night during the ‘Hallelujah wind-up’ he nearly

passed out. “I seemed to be lifted out of myself,” he said,

“and I think that for a time my spirit left my body.” While he

did not faint, “mentally, for a time I was not at home.” When

he regained awareness, he found himself “on the platform among

many others singing and praising God.” “[S]uddenly finding

myself in the midst of a brotherhood with whom I was in

complete accord; without the shadow of a doubt regarding its

divine mission, and then the great meetings climaxing in

scores being converted, all this affected me like wine going

to my head.”[12]

Taiz

also quotes the

National Baptist’s description of a Salvation Army

meeting:

Many of

the soldiers rock[ed] themselves backwards and forwards waving

and clapping their hands, sometimes bowing far forward and

again lifting their … faces, heavenward. The singing was

thickly interlarded with ejaculations, shouts [and] sobs.[13]

Taiz’s

comment is that “Salvationists had created an urban

working-class version of the frontier camp-meeting style of

religious expression.”

All

religious revivals produce their own hymnology. The Christian

Mission used mainly the great Wesleyan hymns Booth and some of

his supporters brought from Methodism – and they had often

been set to the popular song tunes of the previous century.

Many of what today we hear as “great hymns of the Church” were

set to tunes sung in the pubs in the 18th century.

Many of these have been carried forward into the Army’s modern

repertoire. Before long, however, the Army was producing its

own doggerel – and much of it was that. It tended to be set to

the music hall tunes and popular songs of the day, such as

“Champagne Charlie”. In the words of John Cleary, “the early

Salvation Army captured, cannibalised and redeemed the popular

forms of the day, and filled them with messages that spoke of

the love of God for ordinary people and the power of God to

change the world.”[14]

“Penny Song Books” were sold at the meetings. The

War Cry ran

song-writing competitions and printed the results. The

War Cry was also

sold to the congregation so that they could sing the new songs

produced that week. Because many people could not read, the

leader outlined the words of each verse before they were sung.

Many of the songs had choruses, so that the congregations

could pick up the repetitive refrains and join in – as had

long been the custom in the pubs with popular songs as well.

The Officers were instructed:

Remember

that the people do not know any tunes except popular song

tunes and some tunes commonly sung in Sunday Schools, and that

unless they sing, the singing will be poor and will not

interest them much…

Choose,

therefore, hymns and tunes which are known well, and sing them

in such a way as to secure the largest number of singers and

the best singing you can…[15]

John

Rhemick in his A New

People of God explores the significance of the Army’s

“dramatic expression” as a means of reaching working class

people. What a more cultured critic chose to call the Army’s

“coarse, slangy, semi-ludicrous language” was what reached its

target, and popular music provided the right vehicle for such

language.[16]

Paul Alexander, writing on Pentecostal worship, quotes Tex

Sample on how “Pentecostal worship is an expression of

working-class taste because it is in direct contrast to how

‘elitist taste legitimises social inequality’.”[17]

The early Army’s music was the 19th century

equivalent of such religious expression.

The

style and subject matter of the Army’s songs majored on

personal religion; the experience of the individual and

appeals to the individual. “I” and “we” have experienced this;

“You” need to. In the words of Cleary again, the “lyrics were

critically linked to evangelism. Songs for worship were also

songs that spoke to the lost and broken. There were not songs

for the elect body of believers but for the whole lost world

for whom Jesus came.”[18]

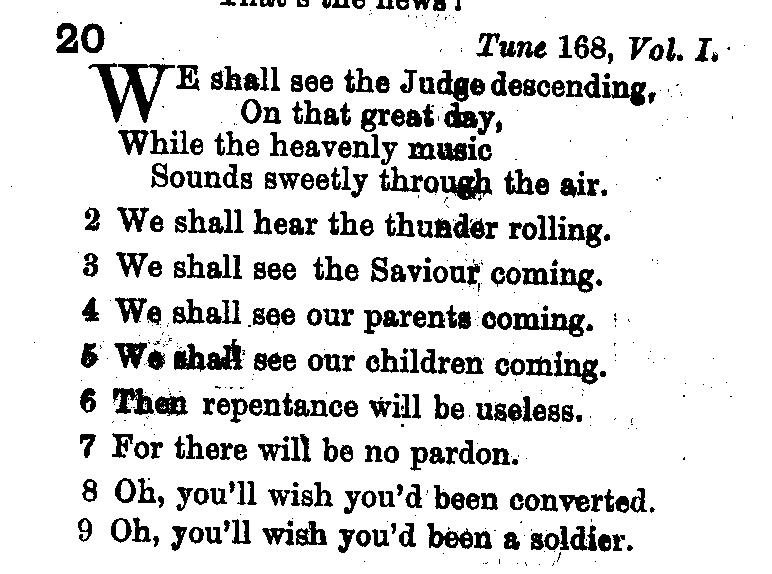

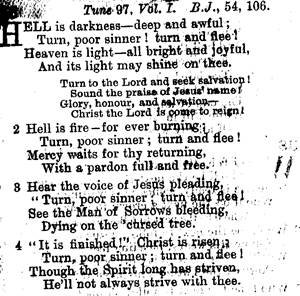

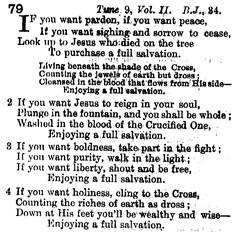

Many of the new songs did not last the distance; we no longer

hear

[19] [19]

Or

A number

seemed to celebrate The Salvation Army itself. On the other

hand, many Army classics by notables like Herbert Booth,

George Scott Railton, Charles Coller, William Pearson, Richard

Slater, Thomas Mundell, and Sidney Cox enriched the Army’s

continuing repertoire. In his memoirs, Bramwell Booth paid

particular tribute to his brother.

Among

the men who stand out prominently as makers of Army music I

must put in first position my brother, Herbert. He, a natural

musician… first originated that kind of music which I may call

peculiarly ours. It is right that he should have special

recognition for the great work he did. He was the creator of

melodies which are now known throughout the world, both within

and outside the Army… His melodies stand unrivalled in their

suitability to Army meetings, and they have earned undying

popularity…[20]

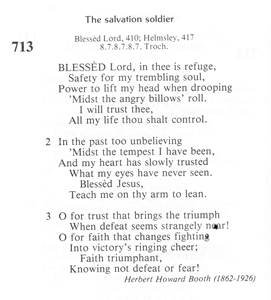

Such a

recommendation is borne out by the retention of no fewer than

22 of Herbert Booth’s songs in the 1986 Song Book, including

the following:

The

following, written by George Ewens in 1880 and first published

in The War Cry in

June 1881, also still appeared in the 1986

Song Book:

At the

same time the older Evangelical and Wesleyan tradition

continued alongside the newer Salvationist style, the book

containing old favourites by people like Fanny Crosby, Richard

Jukes, William Collyer, Henry Alford, and especially by

Charles Wesley. Such writers perhaps provided material more

suitable for the Holiness meetings, perhaps more worshipful,

although the subject matter was less often the attributes of

God than it was the personal spiritual life and struggles of

the worshippers. The emphasis was on joy, triumph and

challenge. Booth admitted in 1904:

I think

sometimes that The Salvation Army comes short in the matter of

worship. I do not think that there is amongst us so much

praising God for the wonders He has wrought, so much blessing

Him for His every kindness, or so much adoration of His

wisdom, power and love as there might, nay, as there ought to

be. You will not find too much worship in our public meetings,

in our more private gatherings, or in our secret heart

experiences. We do not know too much of

“The sacred

awe that dares not move,

And all the inward Heaven of love.”

…

worship means more than either realisation, appreciation,

gratitude or praise; it means adoration. The highest, noblest

emotion of which the soul is capable. Love worships.[21]

Perhaps

the old man was becoming nostalgic for the Wesleyan worship of

his youth.

2.

c. 1900 – c. 1980: The Phase of Routinisation and

Institutionalisation

The

tendency of revival movements is to see themselves as

recreating the original purity of the church. The Army did not

set out to do this – Booth was simply pragmatic – but it came

to believe this is what had happened. A 1921 article claimed:

The

Salvation Army is, in a word, the modern manifestation of

Apostolic religion. For the first 200 years after the death of

Jesus, the Christian Assemblies were very like Salvation Army

meetings. The reading of the Prophets or the Psalms, and

copies of the manuscripts of the Gospels or Pauline letters,

extempore prayers, testimonies – in which the women shared –

and, speaking generally, unconventional as against a set form

of service.[22]

Ironically, by then the unconventional was setting in the

mould of its own conventions. By the early 20th

century the Army’s first great age of expansion and excitement

was over; it was settling down. The period of routinisation

began. If the history of the Church alternates between the

“priestly” tradition, which seeks to secure continuity of an

established pattern, and the “prophetic” tradition, which

seeks to regain the original impetus and spirit which had

created that pattern, at this stage the priestly tradition was

re-asserting its dominance.

Lillian

Taiz has examined the change in the Salvation Army culture in

the United States, but her findings are equally applicable to

the Army in Britain and the old “white” Commonwealth

countries. Firstly (seeing that, in the words of the old song,

“In the open air, we our Army prepare”[23]),

Taiz remarks on the way “at the beginning of the century the

Army started to ritualize its expressive and spontaneous

street meetings by institutionalizing them and creating

carefully scripted performances.” This change is illustrated

from the Men’s Training Garrison curriculum described in the

American War Cry of

14 March 1896. By this time Joe the Turk’s confrontational

antics had become an embarrassment to the high command, which

tried to discourage officers from courting imprisonment and

“martyrdom”, and urged compromise and accommodation with local

authorities. (And Taiz notes that by-mid-century

“Salvationists had largely abandoned their ‘open-air heritage’

and no longer performed their spirituality in the streets.”)[24]

Taiz’s

main point however concerns the Army’s adaptation to changing

culture – both that within which it operated and that found

within its own ranks. The spread of middle-class gentility

affected what the donating public would tolerate from the

Army, and what the gentrifying second-generation Salvationists

would tolerate amongst themselves. While earlier Salvationists

justified their extreme “uncouth, noisy and disagreeable”

informality on the grounds that such methods were necessary to

reach the masses, by the turn of the century the leadership

“took steps to improve the organisations public image by

discouraging noisy, confrontational public performances while

at the same time providing the public with alternative images

of Salvation Army religious culture.”[25]

The same was true of the Army’s homeland; it was no accident

that perceptions of its new-found decorum and professionalism

in Saki’s short story were associated with Laura Kettleway’s

references to the Army’s good works of social reformation –

respectability was important for fund-raising! Taiz draws

attention to the influence of the increasingly important

social operations on the change in the Army’s internal

religious culture. “The social work champions soon realized…

that in a world that enshrined gentility as a standard for

public and private behaviour, the organization could no longer

afford to foster its own marginalization if it meant to

achieve its goals.”

The

Army’s regular congregation was by now composed largely of

Salvationists and regular attendees. The style of meeting

began to change, transmuting from a variety show back into the

typical nonconformist hymn-sandwich, but with more fillings,

or “items” incorporated because the musical sections had to

have their turn. Regulations give a clue: there was one

restricting the band to playing only for the first song in the

Holiness Meeting, because they were beginning to assert their

concert role and play to be noticed. That regulation was not

long in being ignored. Extempore prayer suffered the

stereotyping of word and phrase that accompanies a lack of

preparation. Taiz quotes a Californian thesis to the effect

that “services took on a “traditional ritual and form…

consist[ing] of a call to worship, some offertory, band and

songster special numbers, and a message followed by an alter [sic]

call.”[26]

Taiz

perceptively notes that

in

addition to the transformation of its religious culture,

changes to the Salvation Army by the twentieth century also

reconfigured its religious mission [which] in the nineteenth

century… was “conversion of the lost”. In the twentieth

century … conversion of the heathen masses became the purview

of the social work and was no longer rigorously evangelical…

Salvation Army spiritual work increasingly focussed on “those

already converted and … those who were being nurtured in the

faith.” Like the late-nineteenth-century holiness camp

meetings, Salvationists in the twentieth century began

“preaching to the choir”.[27]

Sermons

began to get longer, and testimonies to diminish, and the

officer to do more and more of the speaking. From time to time

efforts were made to turn the clock back. Even in the 1890s

there was concern that some officers were monopolising the

platform:

It is

rumoured that at some corps the soldiers and sergeants never

have a chance, except in the open-air, the captain reserving

all the indoor meetings to himself. Surely this is an

exaggeration. The General is going to deal with this danger in

a future number. Let us be awake to it, and do our utmost to

avoid the snare.[28]

In 1928

Bramwell Booth wrote to an officer in charge of a corps he had

visited, advising him to, “Rope in your own people in so far

as it is at all possible to take part in platform [i.e.

speaking, preaching] work. If the soldiers and locals felt the

responsibility of speaking to the people the words of life and

truth they would fit themselves for this work. This would

relieve you of some of your platform responsibilities, and

thus enable you to tackle other work.”[29]

And General Edward Higgins wrote, “I am afraid the idea has

sometimes got abroad that Officers are intended to be like

parsons and preach sermons, to monopolize all the time of a

meeting while the people they are supposed to lead in fighting

do nothing.”[30]

Despite regulation and precept, there seemed an inevitable

drift towards a semi-formal churchliness, with parsonical

performances from the officer.

Sadly,

the custom of “lining out” the words of songs continued a

century after all the people could read and had the words

before their eyes – custom once fixed, dies hard. Too many

meeting leaders then felt they had to justify the practice by

preaching a mini-sermon midrash on the words they

superfluously read aloud to their bored congregations. In time

the afternoon “free and easy” evolved into the “Praise

Meeting” in which, where it survived in larger Corps, the Band

played to the Songsters and the Songsters sang to the Band,

and both attempted to entertain the mainly Salvationists and

their bored, long-suffering children who attended, with ever

more esoteric offerings – including transcriptions from the

Great Masters.

The

former Commissioner A. M. Nicol, lamenting the Army’s loss of

its first love in about 1910, gave a depressing picture of an

Army meeting in a London Corps.

I visited a Corps in North London a few weeks ago which stands

in the first grade. I think it is next to Congress Hall in

respect of membership and Self-Denial income. It has an

excellent brass band, a band of songsters, a well-organised

Junior Corps, and the hall in which the meetings are held is

situated in the heart of an industrial population on a site

that is among the best in the neighbourhood. It has an

excellent history and is respected by the people as a whole.

Few people can be found in the neighbourhood to say an unkind

word about it, although if the question was put to them if

they visit the Corps, the answer would be that they "see the

Corps pass by with its band, and some years ago, when Captain

So-and-so was in charge, I occasionally looked in."

What did I see and hear? A small audience, including

officials, of about a hundred people and this Corps has a

membership of some four or five hundred, a humdrum service

without life in the singing, or originality of method or

thought in the leadership, such as would not do credit to an

average mission-hall meeting of twenty or thirty years ago.

But for the music of the band and the singing of a brigade of

twenty songsters the Corps would be defunct. The outside world

was conspicuous by its absence. The audience was made up of

regular attendants.

When the preliminaries were over, the Captain in a strident

voice, as if the heart had been beaten out of him and he had

to make up for the lack of natural feeling by the extent of

his vocal power, announced that the meeting would be thrown

open for testimony. As no one seemed inclined to get up and

testify the surest sign that the Corps was no longer true to

itself he informed the audience that he would sing a hymn. He

gave out the number and the singing went flat. A sergeant,

observing two young men without hymnbooks, went to the

platform and picked up two and was about to hand the same to

the strangers, when he was ordered by the Captain to put them

back. “Let the young men buy books,” he said. I shall not

forget the look upon that sergeant's face; but being

accustomed to the discipline of the Army, and being in a

registered place of worship, he did not express what he

evidently felt.

A song was next sung from the Social Gazette newspaper, one of

the Army’s agency, and the Captain stated as an incentive to

buy that “last week I had to pay five shillings loss on my

newspaper account. For pity's sake buy them up.” The appeal

did not seem to me to strike a sympathetic chord in the

audience.

Testimonies followed. Two or three were so weakly whispered

that I could not catch the words another sign of the loss of

that enthusiasm without which an Army meeting is worse to the

spiritual taste than a sour apple to the palate. Among the

testimonies was the following given by a Salvationist of some

standing:

“I thank God for His grace that enables me to conquer trials

and temptations; I feel the lack of encouragement in this

Corps. My work is to lead the youngsters. In that work I get

no encouragement whatever. The songsters take little interest

in their duties and it is impossible at times not to feel that

they have lost their hold of God. The Corps does not encourage

me, and though our Adjutant will not care to hear me say so,

he does not encourage me.”

A woman got up and screamed a testimony about the lack of the

Holy Ghost and the spirit of backbiting in the Corps, during

which the two young men referred to walked out, and several

soldiers in uniforms smiled, whispered to each other, and the

meeting degenerated into a cross between a school for

ventilating scandal and cadging for “a good collection.” And I

declare that this spirit of the meeting is the spirit of the

Corps in the Salvation Army throughout England and Scotland.

It has ceased to be true to itself, and as a consequence, no

matter how the Army organises and disciplines its forces, the

future of the movement is black indeed, and will become

blacker unless – But that is not my business.[31]

It could

be understood that even though the words and music of the

earlier era survived in the Song Book and usage of this later

time, once the spirit had gone out of the concern in the way

Nicol described, spontaneity would relapse into formalism in

their performance. How far, with ‘redemption and lift’, might

a gradual distancing from genuine working-class roots also

contribute to this change?

Fortunately the worship of the Army in general evidently did

not continue to sink into the morass Nicol described, partly

because of some improvement in its musical skills and perhaps

with the wider adoption of traditional church hymnody and the

production of Army songs of greater merit. The Army’s “hymn

sandwich plus items” format evolved into an instrument capable

of fostering and maintaining its distinctive spirituality –

even though this might appear unusual to outside observers.

The story is told of a BBC producer who had recorded a meeting

at Regent Hall Corps, London, for broadcast in the late 1960s.

He remarked, “That was a very good concert. But tell me, when

do you hold your service for worship?” Writing of Salvation

Army worship towards the end of this period, Gordon Moyles

says:

The

present basis of the Army’s evangelical work is its two public

worship services, conducted in all corps every Sunday. These

too, on the whole, have become predictable, traditionalized

and staid.

The

predictability of Salvation Army worship, only infrequently

thwarted by an imaginative corps officer, lies in the fact

that a meeting format—opening song, prayer, choir and band

selection, testimony period, sermon, appeal—originally adopted

as innovative and lively, is now accepted as sacred and has

become ritual. Salvationists have forgotten that the novelty

attached to early meetings depended not so much on their

format as on their content: lively war songs, sparkling

testimonies, sensational conversions, spontaneous

demonstrations and unexpected diversions were the attractions

that kept the Army barracks filled. This is not to say that

revivalistic techniques have disappeared from Salvation Army

worship; far from it. Revivalist specials still survive; at

Congresses, where charismatic leadership is nearly always

evident, one may still witness emotionally-charged scenes of

repentance and conversion; and there are corps, particularly

in the outports of Newfoundland, where one may still

experience the exuberant evangelism characteristic of all

corps a few decades ago. On the whole, however, and especially

in those corps dominated by middle-class attitudes, routine

and the desire for respectability have tempered the Army’s

exuberant mode of worship. Apart from the peculiar

contribution of the band, there is little in a Salvation Army

worship service which differs remarkably from what one might

encounter in the Sunday services of any other conventional,

conservative conversionist sect.

So much

in Salvation Army practice has in fact become “tradition,” and

therefore sacrosanct, that the Army itself has become a

bulwark of traditionalism. The improvisation and spontaneity

of early Salvationism have been replaced by established

ritual, and some of the results of that early improvisation

have become sacred institutions, enshrined as effectively as

sacerdotalism itself.[32]

John

Cleary suggests that,

Salvation Army methods were so successful that the

Salvationist culture was soon able to close itself off from

the world. By 1912 Army music could be sold only to

Salvationists and Salvationists were not permitted to perform

non-Army music. Brass bands continued to have a powerful

cultural role long after their evangelical influence had

waned.

This is

due in some part to the fact that group music-making is one of

the most creative and cost-effective ways of mobilising a

significant body of people for a purpose that is both

personally fulfilling and spiritually uplifting. Additionally

the brass band is one of the few group musical activities

which is relatively simple to teach, yet allows amateurs

access to the best and most sophisticated music of the genre.

While

this gave Salvationist culture its international cohesiveness

and strength, it turned the culture in on itself. The composer

Eric Ball remembers Bramwell Booth speaking to cadets at the

International Training College of The Salvation Army

[describing the Army] as “A nation within the nations, with

its own art and culture and music”. The Salvation Army

remained largely secure within this culture, insulated from

the currents of the world for almost a century.[33]

In this

respect, the maturing and institutionalised Army became for a

time more, rather than less, sectarian, in the sense that it

increasingly offered an all-embracing social milieu for its

members, which probably went some way towards justifying

Roland Robertson’s description of it as an “established sect”.

Any tendency towards a denominationalising accommodation to

the wider world was delayed by the very strength of its own

sub-culture.

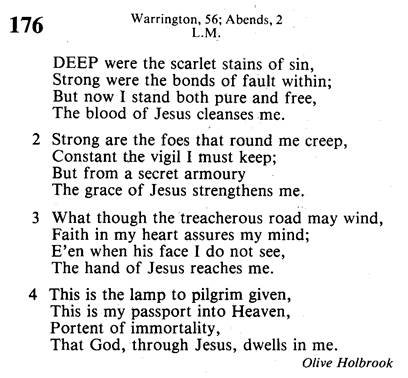

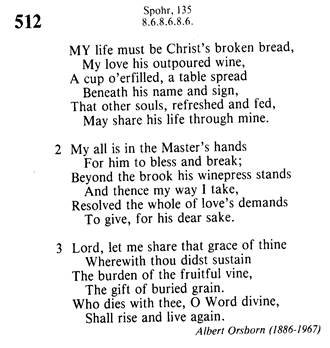

This was

not all loss, however. The Song Books of the twentieth century

provided a widening range of style and theological teaching.

The 1953 and even more so the 1986 edition also sought to

familiarise Salvationists with more hymns from the rest of the

church, some going back to the middle ages and earlier. The

Army also developed a genre of worship songs of its own, still

deeply personal and in fact inward-looking rather than

evangelistic as the early Army songs had been, but equal in

style and content to anything in any tradition. To mention

only two from the 1986

Song Book, firstly Olive Holbrook’s 1934 gem:

And

Albert Orsborn’s well-known 1947 poem:

Many

other writers – Doris Rendell, Ruth Tracy, Catherine Baird,

Will Brand, Bramwell Coles, Miriam Richards and Iva Lou

Samples for example – made their mark.

Besides

such song-writers as those mentioned, there were voices

attempting to recover some freshness and instil some wisdom

even in this period of increasing decadence and routine in

worship. In other words, the prophetic tradition which had

created the Army style in the first place was re-emerging to

critique the pattern into which that style had become set. Of

these, Fred Brown’s The

Salvationist at Worship was a classic exposition.[34]

Frederick Coutts also wrote a series of articles in

The Officer, and

collected in his In

Good Company, addressing the important elements of meeting

leadership: public prayer, the structure of the meeting and

the preaching of the word.[35]

Would that both Brown’s and Coutts’s work were prescribed

reading for all leaders of Salvation Army worship today.

What did

not change with respect to the Army’s own hymnody was its

tendency to focus on the individual’s interior spiritual life.

There was a good deal of “I” and not a great deal of “we”; not

many of its songs explicitly attempted to express the

corporate worshipping life of the community. Nevertheless, at

its best the kind of music and verse available this era went a

long way towards meeting William Booth’s desire for more true

“worship” in Salvation Army gatherings and laid down a

tradition capable of supporting the spirituality of ordinary

Salvationists in a changing world.

While

the matter of Salvation Army architecture has not been

explicitly addressed in this history, the design of the

meeting place – from the earliest co-opted spaces in shops and

theatres, to the purpose-built “Barracks”, to the increasingly

ornate “Citadels” and “Temples”, to the diverse creations of

modern architecture, some under the influence of the wider

“liturgical movement” in the Church – would always have some

influence on the kind of gathering which took place in it. A

rare and valuable recent study of Salvationist architecture in

the United Kingdom at least is that by Ray Oakley in his

To the Glory of God.[36]

3.

c. 1960 to the present day: a phase of diversity, or

another stereotype?

In the

second half of the 20th century a restlessness

crept in upon the established patterns. Some younger

Salvationists began to look to more contemporary models for

Army music-making. The iconoclastic editor of the Danish

War Cry and author

of that country’s territorial history, Brigadier Ketty RÝper,

in her “Reflections on Denmark’s 75th Anniversary,

Is it all Jubilation?” regretted that “Jazz is one of the

modern powers which we – at any rate in Denmark – stifled at

birth and with it many young people whose loss we now pay for

dearly.” Recounting the story of one such group of musicians,

she asked, “Why could we not admit that most of our meetings

are boring… and that progress has ceased?”[37]

With the

advent of Rock’n’Roll and the rise of youth culture, the

guitar began to make its appearance in the Citadel. The Joy

Strings burst upon the astonished Army world in the early

1960s, encouraged by General Coutts. Similar groups began to

appear in other “western” territories, such as USA Western,

Australia and New Zealand. John Cleary suggests this was a

false dawn because the powerful and reactionary forces of

Bands and Songsters were marshalled for the spate of Centenary

Celebrations from 1965. The rock band remained peripheral to

the Army’s vision.

Cleary’s

comment is apt:

In 1965

the huge edifice that was Salvation Army music publishing had

just entered its most mature and sophisticated phase. Both

composers and musicians reached levels that put them on a par

with the best in the secular world. Ray Steadman-Allen’s The

Holy War marked the emergence onto the world stage of serious

Salvation Army brass music. Eric Ball, Dean Coffin, and

Wilfred Heaton, had prepared the way, but in 1965, with the

International Staff Band’s album The Holy War, featuring Ray

Steadman-Allen’s Holy War on one side and Christ is the Answer

– Fantasia For Band and Piano on the other, Salvationist music

had “arrived”.

In this

holy war the Joystrings were simply blown away. Salvation Army

brass musicians around the world welcomed the success of the

Joystrings, but regarded them at best as a novelty, perhaps a

distraction, and at worst as a satanic influence on true

Salvationist culture. Numerous youthful musical aspirations

were crushed by the contempt of local bandmasters, and the

threat of Headquarters to act against those who had not

submitted their work to the Music Board for prior approval.

The Army

of the 1960s failed to recognise that brass bands had come to

occupy the very same niche that church choirs had in the

previous century. Choirs achieved the highest form of musical

art with the best composers writing great works of lasting

value – men like Elgar, Stanford, and Parry. But though of

great merit, they were totally out of touch with the sounds of

the music halls and gin palaces, where the early Salvationists

found their inspiration. Army bands might have been playing

Toccata but it was the Joystrings who touched the public.[38]

It is

also true that the Army of the 20th century

suffered under a disability less problematical in the 19th

– the matter of copyright. Revivalists of the 17th,

18th and 19th centuries could set new

and religious words to whatever popular tunes were being sung

by the people they wanted to evangelise; by the 1960s that

simply was not possible. From Scott Joplin to John Lennon to

Mick Jagger, those melodies were now off limits, even if the

copyright fees could have been afforded. A tremendous link

with popular culture had been cut off; Christian musicians

would have to provide their own and attract attention in a

market never more competitive.

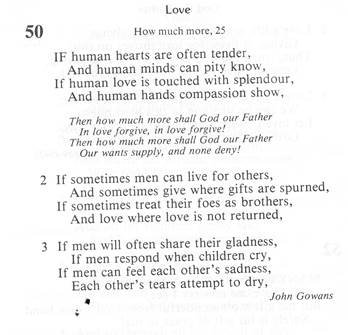

In

succeeding years the great series of musicals with words by

John Gowans and music by John Larsson contributed a score of

lasting classics to the Army’s hymnology.

Indeed, some 20 of Gowans’ songs were included in the

1986 book, including.

Along

with others by such writers as Harry Read, Maureen Jarvis and

Howard Davies, for example, the songs from those musicals have

made a lasting contribution. Unfortunately, these by

themselves were apparently insufficient to inspire an

indigenous Salvationist renewal of corporate worship. An

opportunity seemed to have been missed.

The

Salvation Army, having largely rejected the new life which was

emerging from its own tradition, eventually bought into what

was emerging in a different tradition. It was not until the

1980s that the “Western World” Army began to descend into the

“Worship Wars” which were triggered by the rise of the

charismatic movement and the burgeoning of new songs for yet

another strand of revival. To some extent the Army succumbed

to this influence because of the frustration of many

Salvationists with an ossified tradition, so that they began

looking elsewhere for inspiration – to Pentecostal and

Charismatic styles.

Spasmodic attempts were made to address the need for some

rejuvenation of Salvation Army worship over the years. Colonel

(later General) John Larsson of the United Kingdom presented a

paper on “New Joy in Worship” at a Church Growth conference in

London – touching on what was a crucially divisive issue in

some corps. New Zealand delegate Richard Smith’s Report

stated:

In

introducing this topic Colonel Ian Cutmore spoke of the need

for ‘the kind of worship in our meetings that satisfies the

people who come and will not stay otherwise’. John Larsson’s

emphasis was on the need for real effort to make Sunday

meetings the apex of all we do and so a major priority on the

time of officers, musicians and other leaders in the corps

situation. Colonel Larsson quite strongly stated that many of

our meetings were stereotyped, were uncreative, were

unsatisfying spiritually and were often the result of the

regular turning of a handle to produce a patterned object. The

value of the meeting in actually assisting every person

present to lift their heart to God in praise and in obedience

was much affected by the proper use of suitable words and

music and the creative building of the meeting itself.

He

quoted an American CSM who asked ‘would we want to spend

eternity in a typical Army meeting? The meeting of Christians

together for worship, for praise and for challenge should be

the nearest thing to heaven we experience on this earth.’

GOSH! The possibility of larger corps particularly having a

small group of qualified leaders as a ‘worship team’

responsible for the planning of the first 40 minutes of a

meeting was floated. A major emphasis was the need to adopt

styles of worship and communication which clearly spoke to the

local cultural needs and expectations. The tragedy of the

imposition of a conservative Anglo—Saxon worship and meeting

style upon cultures all around the world was something that

needed attention. Change would demand considerable openness to

allowing liberating changes in terminology, music, and style.

There was a strong feeling that in all territories and

commands there should be an endorsement of the use of

contemporary music in meetings, and the insistence that

officers facilitate inspiring meetings through the use of

music and other means of communication.[39]

Despite

such efforts, it was the Pentecostal-Charismatic mode, the

“Worship Song”, rather than any home-grown Salvationist idiom

which tended to be adopted by Corps in parts of the Western

World. As a result, changes of an altogether more sweeping

kind have overtaken Salvation Army worship in the last part of

the 20th century (and this is from a New Zealand

perspective, and may not be apparent to the same degree

elsewhere). And of course those changes were resisted most

strongly by those who believed that the tradition they

defended was that of the ‘apostolic age’ of the Salvation Army

rather than the creation of the 1950s.

∑

In earlier days Sunday

meetings at Salvation Army Corps had marked “similarities”,

even internationally.

Anyone going to “the Army”

knew in general terms what to expect. Increasingly

however, from the later 1970s, this became less the case.

Meetings were marked now by variety, diversity and

non-conformity rather than the uniformity, conformity and

predictability into which the original Salvation Army free

style had set. Each Corps might be very different in its

worship expression. In some the traditional song-sandwich,

with input from the usual musical sections, would be

encountered. In others, an almost Pentecostal style of meeting

might be found.

∑

Over the course of the last twenty or so

years of the 20th century, the balance of

probability swung in favour of the newer format, so that many

Corps meetings now frequently look and feel more like a

typical “charismatic” church service. The “Song Sandwich” has

been largely replaced in some Corps by a long period of

standing and singing choruses, with many people singing with

hands raised above their heads, followed by a rather long

Sermon. It has to be said, however, that in many cases it

would appear to be the form rather than the spirit of the

charismatic style which has been adopted. Uniformity,

conformity and predictability still prevail, though of a

different flavour.

∑

In some other Corps, worship has changed

though not as much. Following a lurch towards the

charismatic there is now a better traditional and contemporary

balance in these. A period of chorus singing accompanied

by a musical group (guitars, drums and electronic keyboard) is

inserted into the already rather crowded meeting programme,

not uncommonly introduced by, “Now we’re going to have a time

of worship”, as though nothing else which has taken place to

that point qualifies for that description.

∑

There has been a move away from the use

of the Army Song Book

and traditional “hymns of the Church” to use of music and song

material from other, though limited, sources. “Songs of

Praise” and “Songs of the Kingdom” were in turn superseded by

songs of Vineyard and Hillsong provenance, amongst other

material. There is a much reduced theological range in the

sung material, with more of “me” stuff – as there was in the

early Army, though with a different message and often less

theological depth. There can be a concentration on “feel

good”, triumphalist and “prosperity gospel” themes, to the

exclusion of the original Army preoccupation with the needs of

the lost and disadvantaged. It tends to be music for the

self-conceived saints rather than for the sinners. What is

sung in Sunday worship powerfully communicates doctrine, under

the radar as it were, and reinforced through frequent

repetition. Some

material is quite sound; some surely questionable. Much of it

is monotonous, both musically and conceptually; too often

unsuited to congregational singing and boring to listen to. It

also tends to perpetuate the individualistic focus, to the

neglect of the corporate.

∑

In earlier days when almost exclusively

the sung material for Sunday worship came from the

Song Book more

doctrinal checks and balances existed.

Material to be included in each edition was closely

vetted, filtered through the Doctrine Council. Now there is

apparently less careful scrutiny or requirement, other than

the need to avoid copyright infringements.

∑

In some Corps, the choice

of songs is sometimes less in the hands of the Officer and

more as selected by “Worship Leader”. William Booth, with his

insistence on meetings being under the unifying direction of

one person, would not have been pleased.

∑

There is less use of the Brass Band,

which used to make a significant contribution in every

meeting. In the New Zealand territory, Bands are struggling to

survive, even in some larger corps. Their number has probably

halved in the past thirty years. In many corps there has been

an almost complete demise of uniformed music sections – no

band, no songsters, no singing company, no junior band, no

timbrels, etc.

∑

In many Corps the “worship team” has

replaced the Band, Songsters, organ and piano, while in others

there is a relatively comfortable cooperation between the new

and the traditional music groups.

∑

The whole issue of worship styles and

choice of material has been cause of much pain and concern,

along “traditional”/“contemporary” lines. Some older, more

traditional Salvationists feel betrayed and abandoned.

∑

There appears to be a dearth of public

testimony from people who are not officers or aged senior

soldiers, and opportunity is seldom given for such expression

of experience.

∑

In the early 1960s, when Television was

introduced to New Zealand, there was within a year or two a

change in attendance patterns; instead of the morning meeting

being the smaller and the evening meeting the larger, with

greater likelihood of non-Salvationists attending, their

attendances were reversed. By the 1990s, the evening meeting

had begun to disappear entirely, despite attempts in places to

make it a specialised “youth” meeting. The collapse of

intentionally focussed “holiness” and “salvation” meetings

into one event had implications for what was taught and

preached. Traditional Wesleyan Holiness teaching largely

disappeared – although other reasons have contributed to this

change.

∑

Technology plays a larger

part: e.g data projectors, projected song material,

‘powerpoint’ sermons, video clips, are common. (And

sermons straight off the internet, not invariably taken from

doctrinally impeccable sites, have become all too familiar.)

∑

In a few larger corps, multiple

congregations have been attempted, with a number of relatively

discrete congregations meeting at separate times.

In an

attempt to provide some resources for development of worship,

in 2003 General Larsson appointed Colonels Robert and Gwenyth

Redhead, domiciled in Canada, to an international role as

“General’s Representatives for the Development of Evangelism

and Worship through Music and other Creative Arts”. This

innovative appointment capitalised on the Redheads’ personal

giftings but its effectiveness was really dependent upon their

individual influence and example in the course of their

extensive travels conducting meetings and workshops. Only so

much could be done this way, and in any case the role did not

survive their retirement in 2005.

This

outline has really only referred to the “Western World” – and

only to those parts with which I am familiar. Furthermore,

some parts of that World might not recognise what I have

described. Attending a small corps in Washington DC, USA, in

2004, I felt I had time-travelled back to the corps of my

adolescence in 1950s New Zealand. But 80% of Salvationists are

to be found today in the “Developing World”. While the

“colonial” influence of western officers as missionaries and

leaders long imposed a song sandwich model and acclimatised

versions of European hymns on these territories, are they now

breaking the mould and exploring indigenous ways of being

Salvationists. Indeed, 35 and more years ago in

Rhodesia-Zimbabwe there was a world of difference between the

type of meeting and singing customary in the largely

missionary-led Howard Institute Hall and the altogether more

boisterous and triple

forte celebration at a village corps, where people did not

sing without simultaneously dancing, and there were as many

vocal parts as in Tallis’s “Spem in Alium”.

Now that

a new Song Book is

appearing, it will be interesting to see how all these special

interests are to be accommodated.

John

Cleary asks of the way forward:

How do

we bridge the gulf between contemporary style and theological

substance? There is in fact a direct link between the lyrical

and musical styles of today and the revolutionary message of

William Booth and John Wesley. It can be found where

evangelicals give hope to the most oppressed… The black

spirituals spring out of a combination of the heart-felt cry

of the oppressed and the world-redeeming hope of Wesley and

Finney. It is music that is grounded in the love of God,

speaks with the voice of the prophet, shows all the tenderness

of Jesus and moves through the power of the spirit. It is no

accident that out of this musical form sprang the most popular

musical forms of the 20th century; Blues, Jazz, Rock and Soul.

This is music that speaks from heart to heart. It lives with

sorrow and pain yet sings of hope.

Black

Gospel music is the bedrock of contemporary Christian music.

The Salvation Army has missed this connection twice before.

Once in the 1910s, when having so successfully embraced the

sounds of the secular English Music Hall and the American

Minstrel shows of the 1880s, we turned our back on the

religiously based Blues and Jazz of the early 1900s. And again

in the 1960s, the Joystrings reconnected Salvationists with

popular culture at a critical turning point in the modern

world. Unfortunately the movement was deaf to the message.

The

consistent path for the Salvationist is radical engagement.

The Salvation Army needs to embrace contemporary Christian

music. It needs to learn the lessons of its own history and

infuse that music with a comprehensive sense of compassion and

care, which belongs to the roots of Gospel music and the

origins of The Salvation Army.

It is

something of an irony that at the very time some Salvationists

are questioning its mission, the evangelical church is

rediscovering its need for a theology that engages with the

world. Evangelists such as Philip Yancy and Tony Campolo in

the United States, magazines like

Christianity Today

and Christian History

are turning to the great evangelical revival for inspiration.

The evangelical churches are recovering the message of William

and Catherine Booth and the early Salvation Army.[40]

In

conclusion, we look back to our introductory suggestion that

we might distinguish three very general periods or phases in

Salvation Army worship style, roughly parallel to the

sociologists’ analysis of Salvation Army history.

∑

We might take the first phase,

enthusiasm, as an example of the “prophetic” attempt to

recover first principles, in this case of the evangelisation

of the poor and disadvantaged.

∑

The second phase, of routinisation, can

be seen as an example of the reassertion of the “priestly”

function of stability, the maintenance and preservation of

what has been achieved.

∑

In the third phase there is a tension

between the “prophetic “and the “priestly” and it is not clear

whether they will learn to co-exist or one will achieve

dominance for a period. The newer, charismatically-influenced

worship style was itself the product of a revival movement,

even as the “old Army” was in its time. However, by the time

the charismatic movement came to influence the contemporary

Army it was already losing its original momentum and turning

into another example of a “priestly” phase of church life. Its

music is in the course of becoming as esoteric and out of

touch with the world as that of Herbert Howells or Ray

Steadman-Allan. (How many non-Christians tune in to

“Christian” radio? Or how many Christians, for that matter?)

The Salvation Army has therefore “copped a double whammy”; it

has been the locus of a struggle between two equally

controlling and outdated modes. Perhaps Alice Cooper would be

a better model than Hillsong of a genuinely spiritual voice in

the contemporary world. A real diversity of source and

expression, encompassing traditional Salvation Army classics,

music from the charismatic tradition and other contemporary

hymns (of which the Army is largely unaware) would be a

helpful thing.

John

Cleary’s analysis of the present challenge suggests that the

Salvation Army needs to look to its own roots for the

inspiration and resources whereby it might renew its mission

and worship. Perhaps a weakness in his argument is the

assumption that all Army music must be evangelical and

therefore to engage the “world” it must be focussed on and

stylistically drawn from popular culture. The difficulty with

this, as it has been since the second and third generations of

Salvationists, is that the Army also needs to keep its own,

home-grown constituency engaged. It needs therefore somehow to

maintain a smorgasbord of styles, fostering mutual acceptance

and toleration, in order to keep the whole together.

[1]

William Baggaly,

A Digest of the

Minutes, Institutes, Polity, Doctrines, Ordinances and

Literature of the Methodist New Connexion (London:

Methodist New Connexion Bookroom, 1862) p. 230.

[2]

Robert Sandall,

History of The Salvation Army (London: Nelson,

1947) I, 237-8.

[3]

W. Bramwell Booth,

These Fifty

Years (London: Cassell, 1929) 193.

[4]

Sandall,

History I, 114-5.

[5]

Sandall,

History I, 77-8.

[6]

Orders and

Regulations for The Salvation Army

(London: The

Salvation Army, 1878) 54-5.

[7]

Orders and

Regulations for The Salvation Army

(London: The

Salvation Army, 1878) 112-114.

[8]

Catherine Bramwell Booth,

Bramwell Booth

(London: Rich & Cowan, 1932) 90.

[10]

The Doctrines

and Discipline of The Salvation Army

(London: The

Salvation Army, 1881) Section 32.

[11]

Sandall,

History I, 209.

[12]

Lillian Taiz,

Hallelujah Lads & Lasses: Remaking the Salvation Army

in America 1880-1930 (Chapel Hill: University of

North Carolina, 2001) 76, quoting James W. Price,

“Random Reminiscences,” 1889-99, 78, RG 20.27, SA

Archives (USA).

[13]

Taiz,

Hallelujah Lads, 77, citing the London

War Cry, 10

July 1880, 4.

[15]

Orders and

Regulations for The Salvation Army

(London: The

Salvation Army, 1878) 53-4.

[16]

John Rhemick, A New People of God: A Study in

Salvationism (The Salvation Army: Des Plaines Ill,

1993) 167.

[17]

Tex Sample,

White Soul: Country Music, the Church and Working

Americans (Nashville Tenn: Abingdon, 1996)

76, quoted in Paul Alexander,

Signs and

Wonders (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2009) 32.

[18]

Cleary, “Salvationist Worship…”

2.

[19]

The Salvation

Soldiers’ Song Book,

Colony Headquarters, New Zealand. (Undated, but with

the name of Brigadier Hoskin, who was Colony Commander

1895-98, on the back cover.)

[20]

Bramwell Booth,

These Fifty Years, 229-30.

[21]

William Booth, “The Spirit of Burning Love” in

International

Congress Addresses, 1904 (London: The Salvation

Army, 1904) 139-40.

[22]

“Torchbearer”, “The Salvation Army and Sacerdotalism”,

The Salvation

Army Year Book, 1921, 22.

[23]

From Fanny Crosby’s 1867 hymn,

readily adapted by the Army in its 1878 Song Book.

[24]

Lillian Taiz,

Hallelujah Lads & Lasses: Remaking the Salvation Army

in America, 1880-1930 (Chapel Hill NC: University

of North Carolina Press, 2001) 142.

[25]

Taiz,

Hallelujah Lads,

145.

[26]

Taiz,

Hallelujah Lads,