|

Hierarchy and Holiness

by Major Harold Hill

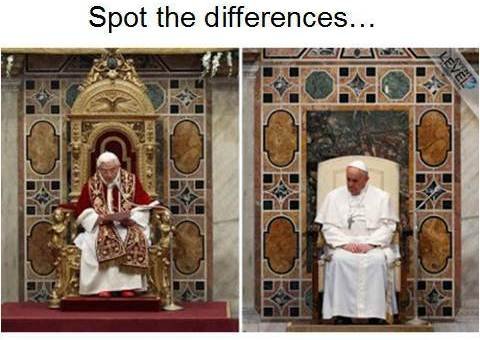

Remember those cartoons where you are invited to

Spot the Difference?

Here’s one.

We hear of Pope Francis deserting the luxurious Papal

apartments to hang out in a sort of boarding house for

priests, scooting round Rome in a little old Ford Fiesta

instead of using an armour-plated Mercedes, laying aside

ornate vestments and handmade red shoes in favour of a simple

cassock and his old scuffs. He’s sending signals.

We’re used

to receiving and

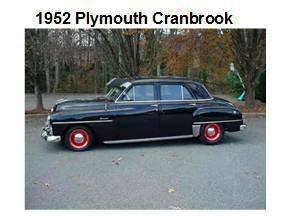

interpreting such signals. I remember in my callow youth

asking the formidable Commissioner Robert A. Hoggard whether

he didn’t think his snazzy new 1952 Plymouth Cranbrook was a

little too flash for the Salvation Army to be seen going about

it? (I do not know where I got

that idea from!)

He replied, “Oh, no, not at all. Where I come from [USA

Western territory], this is a Lieutenant’s car. Commissioners

drive Cadillacs!”

Then when I went to London in 1970 I noticed that whereas a

mere Commissioner drove an Austin 1100, the Chief of the Staff

drove an Austin 1800, and the General was driven about in an

Austin 3 litre.

Years later in the USA Salvation Army National Archives I read

the correspondence between a Territorial

Commander and a

Lieutenant who was threatened with dismissal and was

eventually sacked because he wouldn’t dispose of his

Oldsmobile (I think it was), deemed

not to be a

“Lieutenant’s car”. I kid you not.

(Perhaps there was

another back-story.)

They were all signals. What these examples signalled was

“hierarchy”. The difficulty I found lay in reconciling those

signals with Jesus’ words, “That is the way the VIPs and

Celebrities of this earth go

on… Don’t be

like that!”[1]

All this may be juvenile taking of the mickey, but what was

signalled was no light matter. My subject, for which I am

indebted to Caroline, is

Hierarchy and

Holiness. I need to

talk about each in turn, and then about both together.

Hierarchy

Firstly, we’re familiar with the concept of

Hierarchy. A

pyramid, with the broad base of plebs at the bottom, rises

through more restricted levels of middle-management, to the

solitary splendour of the occupant of the apex. In his study

of Milton’s Paradise

Lost, C.S. Lewis explains how pre-modern society was quite

unambiguously and unapologetically structured hierarchically.

It wasn’t considered just a convenient and effective way of

constructing work relationships; it was seen as inherent in

nature. Lewis wrote,

Degrees of value are objectively present in the universe.

Everything except God has some natural superior. The goodness,

happiness and dignity of every being consists in obeying its

natural superior and ruling its natural inferiors… Aristotle

tells us that to rule and to be ruled are things according to

nature. The soul is the natural ruler of the body, the male of

the female, reason of passion. Slavery is justified because

some men are to other men as souls are to bodies (Politics,

1, 5).[2]

Now I’m not about to argue the anarchist or Leveller converse,

that Jack’s as good as his master, but need to remind you that

our whole clerical system in the church derives from this

hierarchical

conception of

reality, which we no longer take for granted today.

The early church was relatively egalitarian. It had leaders

but no priests. Over its first few centuries, as it

institutionalised, it accommodated to traditional religious

expectations, to hierarchical society and to the Roman state.[3]

The Church took on characteristics incompatible with its

founding vision of free and equal citizens in the Kingdom of

Heaven (rather like Israel’s earlier ideal of being a nation

of kings and priests).[4]

When society becomes too unequal and is at risk of breaking

down, Christianity seems to rediscover its roots and new

groups with a greater emphasis on internal equality are

formed.[5]

Thus renewal in the Church often coincides with disruption in

society as whole, or dissatisfaction of marginalised groups.

Both the Christian Mission and the 614 movement started in the

slums. Further, nearly all sectarian movements including and

from the early church on – monasticism, the mendicant orders

of friars, the Waldensians, the reformation churches and

sects, the Methodists and the Pentecostals, have begun as

“lay” movements, acknowledging little distinction of status

between leaders and led, but nearly all have ended up

controlled by priestly hierarchies, whether so called or not.

The more institutionalised the body becomes, the greater

degree of clericalisation and “hierarchisation” likely.

Bryan Wilson sums up:

What does appear is that the dissenting movements of

Protestantism, which were lay movements, or movements which

gave greater place to laymen than the traditional churches had

ever conceded, pass, over the course of time, under the

control of full-time religious specialists… Over time,

movements which rebel against religious specialization,

against clerical privilege and control, gradually come again

under the control of a clerical class… Professionalism is a

part of the wider social process of secular society, and so

even in anti-clerical movements professionals re-emerge. Their

real power, when they do re-emerge, however, is in their

administrative control and the fact of their full-time

involvement, and not in their liturgical functions, although

these will be regarded as the activity for which their

authority is legitimated.[6]

Religious authorities usually claim some “spiritual”

legitimation for their human behaviour. For example, in the

church there grew up a tradition that ordination indelibly and

irreversibly changes a person’s essential, ontological

character, just as baptism (or conversion, in the Evangelical

tradition) is believed to do. The second Vatican council stood

in a tradition stretching back to Augustine of Hippo (who died

almost 400 years after Jesus) when it asserted that

The common priesthood of the faithful and the ministerial

priesthood… differ essentially and not only in degree.[7]

Others deny that. Emil Brunner says that

All minister, and nowhere is to be perceived a separation or

even merely a distinction between those who do and those who

do not minister… There exists in the Ecclesia a universal duty

and right of service, a universal readiness to serve and at

the same time the greatest possible differentiation of

functions.[8]

Nevertheless, whether we hold that clergy are essentially

different from lesser mortals or we claim to believe in

equality, the end result is often the same. Miroslav Volf

noted that even in the contemporary unstructured house church

movement:

“A strongly hierarchical, informal system of paternal

relations often develops between the congregation and the

charismatic delegates from the ascended Christ.”[9]

Whether in the Exclusive Brethren or the “Shepherding”

movement, you know who is the boss. Having clerics does not

necessarily involve clericalism. Not having clerics does not

necessarily mean clericalism can be avoided. Office itself,

formal or informal, inevitably confers power and power offers

at least possibility of those who exercise it “tyrannising

over those allotted to [their] care”.[10]

(Peter was aware of the danger!)

In Walter Brueggemann’s

Prophetic Imagination, the alternative, prophetic

community of Moses is contrasted with the “royal

consciousness” of Egyptian Empire. Within 250 years of the

Exodus from Egypt, the establishment of Solomon’s Empire

represented the rejection of that free association of

Israelites and a return to structures of oppression.[11]

In the same way, the process of institutionalisation and

clericalisation in the church can be seen as a successful

reconquest of the new community by the old structures of

domination and power. These in turn may be subverted in due

course by renewed egalitarianism.

My argument is that the Salvation Army’s own development

conforms to this general pattern. I won’t rehearse tonight the

steps by which this came about – you can read my book if you

want the details; Salvationist Supplies still has some copies![12]

I’ll say just one thing: The Salvation Army doesn’t accept

that becoming a priest or a bishop (or, officer or an officer

holding “conferred-rank”) alters your Christian “character”,

but in practice it behaves as if it did. The most recent

expression of the Army’s clericalisation is found in the

adoption of “ordination” by General Arnold Brown in 1978.

Ordination came about originally because of the Church’s

adoption of the concept of “ordo”, the class structure of the

Roman Empire. The Army doesn’t endorse that, so why play dress

ups?

This is not saying we need no structure. Any human society

needs some form of order to avoid falling into either anarchy

or tyranny. A society called into being around some founding

vision requires some means of maintaining what in the church

is called “apostolicity” – authenticity derived from

faithfulness to a founding vision. That is part of the role of

leadership, which a hierarchy can provide. The danger with

leadership, however, is that rather than being merely a means

of maintaining authenticity, it can come to identify itself as

central to it, the means becoming the end. That is

clericalisation. That is the shadow side of hierarchy.

Holiness

Now, leaving Hierarchy for the present, what about

Holiness?

When I was growing up it was never explicitly stated but

somehow assumed quite widely that holiness was a matter of

personal morality, spirituality, piety and general “niceness”.

It tended to be regarded as a field for the

spiritually

athletic, the virtuosi, rather than the general

run-of-the-mill Christian like me. It was an advanced degree,

an honours course, to which a few went on after getting their

BA, or Born Again. Wesleyan Holiness, our traditional take on

the subject, has lost credibility over the years, partly

through being inadequately taught. The result, to adapt G.K.

Chesterton, was that rather than being tried and found too

hard, it was thought too hard and not tried. Put to one side

the tedious “shibboleth-sibboleth” debate about “crisis”

and/or “process” aspect of Holiness – I’m not concerned with

that!

Holiness has suffered, amongst other things, from an

unbalanced, individualistic interpretation of the gospel.

In our

Evangelical tradition Salvation, which includes holiness, was

about me, getting

me saved and

sanctified and going to heaven. When we read that holiness is

“the revealing of Christ’s own character in the life of the

believer”,[13]

that’s true, but it’s not the whole truth. That’s still about

me. In western

countries, that individualistic focus of our mindset was

intensified in the later twentieth century under the influence

of New Right economics when our whole society took a turn away

from social responsibility and towards the sanctification of

individual greed as the driving force of society, with the

excuse that by a process of trickle-down, all boats would rise

on the flood-tide of prosperity. That hasn’t just changed our

economic arrangements; it has increasingly permeated our

world-view. It didn’t alter our doctrine of holiness; it

merely completed the total skewing of our perception of what

holiness involved. That is, that it was just a matter for the

individual.

We glibly dismiss the people of Jesus’ day as preoccupied with

his setting up an earthly Kingdom, whereas his

Kingdom was “not

of this world”. We, with the benefit of hindsight, know so

much better than they did what he was on about.

Yes? No, not entirely.

If we read Jesus without our inherited spectacles of

individualism, we notice that a

lot of what he

talked about was not

about the saving and sanctifying of the individual as an end

in itself but about redeeming society as a whole. He came

preaching and teaching about the Kingdom of Heaven, which

wasn’t pie in the sky for me when I die, but the

redemption of

this

world so that it

would more closely resemble how God intended it to be. “Your

Kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as in heaven,” is

what he taught us to pray. A renewed emphasis on social

justice is a rediscovery of this dimension of holiness;

embraced by many, while many others regard it as a distraction

from the real spiritual business of saving souls.

Salvation, of which holiness

is a subset,

part of a continuum, is about

Shalom: wholeness,

peace, well-being, and

righteousness – which did not mean being goody-goody

two-shoes, but meant being in a

right relationship

with ourselves, with others and with God. Which is why John

Wesley exclaimed, against the notion of the solitary seeking

of perfection, that, “there is no holiness but

social holiness.”

Christianity is a team sport, not a narcissistic individual

hobby like body-building.

At the personal and interpersonal level, holiness is expressed

in what William Temple described as the “true test of

worship”: “not whether it makes us feel better or more holy or

more at peace… [but]

what it does to our lives; whether it makes us more unselfish,

more easy to live with, more efficient in our work.” That is

“becoming more like Jesus”. At the macro-level, a concern for

social justice is integral to a concern for personal holiness;

it is making the earth more like heaven. I cannot be holy and

still content that others suffer injustice. At Finney’s

campaign meetings 150 years ago, seekers were directed from

the “Mourners’ Bench”, either to the table at which they could

sign up to the anti-slavery campaign, or to the table at which

they could sign up to work for female emancipation and women’s

rights. And if they were unwilling to do either, they were

sent back to their seats: it was not believed that they’d made

a real decision to follow Christ.

So the polarisation we frequently encounter, between “saving

souls” and “serving suffering humanity”, as though either one

of these were more central, a loftier aim, and the other

merely optional window-dressing, is a false dichotomy.

As William Booth put it, there needs to be “Salvation

for Both Worlds”.[14]

Birds do not fly far on one wing only. If we want biblical

underpinnings of this argument we need look no further than

Jesus’ summary of the great commandments – to love God, and to

love our neighbour as ourselves.[15]

He said the second was “like the first”; it wasn’t a minor,

optional extra.

Hierarchy and

Holiness?

Hierarchy is a way of structuring relationships; holiness is

to do with the nature of those relationships.

One is to do

with form; the other is to do with essence. So the question

needs to be asked, how holiness may be expressed in socially

just relationships. Can our institutional structure, our

hierarchy, facilitate loving behaviour, by all involved, so

that we love all our associates, both those in authority over

us and those subordinate to us, as we love ourselves? This is

at the heart of the question of what holiness has to do with

hierarchy.

I suggest that

that the hierarchy created by clericalisation is a form which

can make its imprint on the essence instead of the essence

being expressed in the form. That’s a very sweeping

generalisation and therefore only partly true, but let’s tease

out the tension between hierarchy and holiness.

Firstly, the hierarchical structure which clericalism has

created can foster a spirit incompatible with “servanthood”

Jesus modelled and taught; it can undermine relational

holiness and so threaten the kind of community Jesus calls

together.

Secondly, by concentrating power and influence in the hands of

minority, clericalisation can disempower the majority of

members of Church. That can co-exist with patronising the

brethren but not with loving the brethren. It can therefore

diminish the Church’s effectiveness in mission.

Of the first adverse

effect, you could supply your own examples, but if it’s any

help, Bramwell Booth was aware of the danger long back.

In 1894 he was complaining that “the D.O.’s [Divisional

Officers] are often much more separate from their F.O.’s

[Field Officers] than they ought to be. Class and caste grows

with the growth of the military idea. Needs watching.”[16]

Thirty years later he was still anxious about Divisional and

Territorial leaders in that “they are open to special dangers

in that they rise and grow powerful and sink into a kind of

opulence…”[17]

(Unhappily, Captains are just as prone to this as Colonels.)

General Albert Orsborn acknowledged to the 1949 Commissioners’

Conference that

dissatisfaction and decline… is blamed on our system of ranks,

promotions, positions and differing salaries and retirements…

that it has created envy and kindred evils and developed

sycophancy, ingratiation, “wire-pulling”, favouritism, etc… It

is a sad reflection that we are in character, in spirituality,

unable to meet the strain of our own system.[18]

Koinonia

and just social relationships are difficult to maintain within

that system. All of which is to say that it is in the nature

of systems to get in the way of the reason they exist.

If the doctrine of holiness is not lived as well as

talked about, human nature will take its course, and a system

which

actually encourages it to do so, as

ours tends to, requires extra vigilance.

And the second adverse effect, the disempowerment of the many

by the exaltation of the few?

The American Nazarene sociologist Kenneth E. Crow summed it

up: “Loyalty declines when ability to influence decision and

policies declines. When institutionalization results in

top-down management, one of the consequences is member apathy

and withdrawal.”[19]

Likewise the Indian Jesuit Kurien Kunnumpuram claimed that

“the clergy-laity divide and the consequent lack of

power-sharing in the Church are largely responsible for the

apathy and inertia that one notices in the bulk of the laity

today.”[20]

Does our structure likewise disempower the Army’s

soldiery? The root of disempowerment is a lack of respect for

others, and that is, again, evidence of a failure to love

one’s neighbour as oneself.

It would be difficult to say whether clericalisation had led

to a loss of zeal, or loss of zeal had been compensated for by

a growing preoccupation with status, or whether each process

fed the other. There is a paradox here: the military system,

quite apart from the fact that it fitted Booth’s autocratic

temperament, was designed for rapid response, and is still

officially justified in those terms. The Army’s first period

of rapid growth followed its introduction. It caught the

imagination for a time. However the burgeoning of hierarchical

and bureaucratic attitudes came to exert a counter-influence.

The reason for success contained the seeds of failure. The

longer-term effect of autocracy was to lose the loyalty of

many of those hitherto enthusiastic, and to deter subsequent

generations, more habituated to free thought and democracy,

from joining.

Clearly I’m talking about what we may loosely call the

“Western” Army. In Africa and India the Army is still

expanding rapidly and

is also extremely rank-conscious! The cultures are different.

I do not believe that in

our culture, our

salvation lies in the hair of the dog that bit us.

Furthermore, the abuses of power already evident in the third

world Army suggest that there will be a reckoning to pay there

too. Faced with a flagrant example of such abuse in the past

year, a Zimbabwean Salvationist wrote, “The

Salvation Army now frightens me… We now know we are waging war

against a Monster… Our very own church! Am now very ashamed to

wear my uniform and so are many other people.”[21]

Such a reaction does not augur well for continued expansion.

Unfortunately clericalism is to clergy as water to fish,

wherever we live. It’s so pervasive we don’t recognise it, but

as a soldier working at THQ once said to me, “It’s in our

faces all the time!”

How may the ill-effects of the hierarchical system be

mitigated? That

is, how may the essential holiness still be

expressed through this form?

Leadership is indispensable to the effectiveness of any

movement; it’s a given. Structure is necessary; it will happen

anyway, and it needs continuity, accountability and legitimacy

to mitigate the effects of unrestrained personal power.

There are two ways the problem can be approached: one is

structural, the other attitudinal.

In 2002 the first edition of the Salvation Army’s Doctrine

Council’s publication,

Servants Together, made the following suggestions for

structural change:

What actions does Army administration need to take in order to

facilitate servant leadership? Here are some of the important

ones:

·

Develop non-career-oriented leadership models.

·

Dismantle as many forms of officer elitism as possible.

·

Continue to find ways to expand participatory decision-making.[22]

I believe structural change is essential but none of us is in

a position to make it, and you know it’s not going to happen.

In fact that whole paragraph quoted was deleted from the

second, 2008, edition of

Servants Together.

And wherever else the expression “participatory

decision-making” was used, that was replaced by “consultative

decision-making”.[23]

Do you draw any conclusions from those excisions? Perhaps none

of the structural changes suggested might have made any

difference anyway.

In 1996 when Commissioner (later General) John Larsson was

about to conclude his term as Territorial Commander in New

Zealand, he kindly invited me to arrange the annual Executive

Officers’ Councils as a training seminar. With his approval I

engaged Gerard La Rooy, a Heinz-Watties executive and

management guru, to lead sessions on “Flatter Structures” in

management. By citing awful examples from the realm of

business and expressing astonishment at the laughter as the

officers recognised the same scenarios as found in the

Salvation Army, he led them to consider how the work might be

enhanced by flattening out some operations of the hierarchy.

Some “participative decision-making” might have been involved.

They got as far as drawing up suggestions for change – all

pretty minor but likely to improve efficiency – and nominated

a working party to continue developing the theme in the coming

weeks. Then it all went quiet. After some weeks I asked the

Chief Secretary, Hillmon Buckingham, “What happened?” “Ah,” he

replied, “For the week after the Councils I had a succession

of senior officers come to my office saying, ‘We might have

got a bit carried away with this flatter structures business…

I think we should be a bit careful…’” And so we were. Even the

slightest tinkering with the structure of hierarchies can

produce severe symptoms of insecurity.

And the truth is that no structure can ensure that we love our

neighbour – whether our senior in the command structure or our

subordinate – as ourselves. That leaves our

attitudes. The 2002

text of Servants

Together made one other suggestion:

·

Teach leaders to be servants by modelling it.[24]

That was also deleted from the 2008 edition.

I guess it was too much like Jesus, or Paul… in a word,

subversive. Too often, the mantra “Servant Leadership” is an

oxymoron. Servant is as servant does. To model

servanthood is the only suggestion most of us can aspire to

implement, but it is also the most important. And where

opportunity affords, to name and challenge its antithesis, its

shadow, which is the abuse of power.

Because power is at

the heart of the matter. Money, sex and power are said to be

the three pitfalls for clergy, but the first two are usually

only means to, or expression of, the third. Hans Rudi Weber

wrote that “Jesus transforms the love of power into the power

of love.”[25]

Sometimes we get it the wrong way round.

Power, like steroids taken by an athlete, may enhance

performance but exact a long-term cost.

So the question is whether holiness, both personal holiness

(which is being like Jesus) and corporate holiness (which is

the application of the principles of social justice to our

structural relationships, so that the Body of Christ can be

like Jesus), can redeem a hierarchical institution?

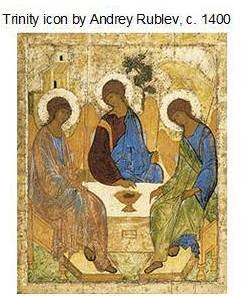

Over

the years the doctrine of the Trinity has been presented in

such a way as to support a hierarchical conception of both God

and the Church. Here is a medieval Swedish Gothic

representation of the Trinity. You can see who is in charge. Over

the years the doctrine of the Trinity has been presented in

such a way as to support a hierarchical conception of both God

and the Church. Here is a medieval Swedish Gothic

representation of the Trinity. You can see who is in charge.

But there is another tradition, of what is termed the

perichoretic trinity. Here is an ancient icon. Who is in

charge here?

So, is there a way in which Hierarchy may be Holy? If so, the

Hierarchy may not look like we expect. Paradox is involved.

Colonel Janet Munn, being interviewed last month, spoke of the

paradox in Jesus’ combination of humility and boldness (by

contrast with the frequently found human combination of

arrogance and cowardice). She noted that “Servanthood requires

humility; leadership demands boldness.”[26]

Jesus in fact deconstructed leadership along these lines: “I

do not call you servants any longer, because a servant does

not know what his master is doing.

Instead, I call you friends...”[27]

Mind-blowing it may be, but he is inviting us to gather round

that table. The implications for both hierarchy and holiness

are worth considering.

[2]

C. S. Lewis, A

Preface to Paradise Lost (London: Oxford University Press, [1942]

1960) 72-3.

[3]

A comprehensive account of the process is found in

Colin Bulley,

The Priesthood of Some Believers: Developments from

the General to the Special Priesthood in Christian

Literature in the First Three Centuries (Carlisle:

Paternoster, 2000).

[4]

Exodus 19.6; Revelation 1:6; 5:10.

[5]

The egalitarian vision remained, in David

Martin’s terms, “a store of explosive materials

capable of fissionable contact with social

fragmentation” so that “schism is inevitable and

rooted in the nature of Christianity itself as well as

in the nature of society.”

David Martin,

Reflections on Sociology and Theology (Oxford:

Clarendon Press, 1997) 42-3.

[6]

Bryan Wilson,

Religion in Secular Society (London: C.A. Watts,

1966) 136.

[7]

“Dogmatic Constitution of the Church, Article 10” in

Austin Flannery (Ed.)

Vatican Council

II: The Conciliar and Post-Conciliar Documents

(Collegeville Min: Liturgical Press, 1975) 361.

[8]

Emil Brunner,

The Misunderstanding of the Church (London:

Lutterworth, 1953) 50.

[9]

Miroslav Volf,

After Our Likeness: The Church in the Image of the

Trinity (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1998) 237.

[11]

Walter Brueggemann,

The Prophetic

Imagination (Minneapolis:

Fortress Press, 2nd edn 2001) 23.

[12]

Harold Hill,

Leadership in the Salvation Army: a case study in

clericalisation (Milton

Keynes: Paternoster, 2006).

[13]

Frederick Coutts,

The Splendour

of Holiness (London: Salvation Army, 1983) 41.

[14]

William Booth, “Salvation for Both Worlds”,

All the World,

5 (January 1889) 1-6, reprinted in Andrew M. Eason and

Roger J. Green (Editors),

Boundless

Salvation: the shorter writings of William Booth (New York: Peter Lang, 2012) 51-9.

[16]

W. Bramwell Booth, letter of October 1894, in

Catherine Bramwell Booth,

Bramwell Booth

(London: Rich & Cowan, 1932) 218.

[17]

W. Bramwell Booth, letter to his wife, 27 April 1924,

in Catherine Bramwell Booth,

Bramwell Booth,

437.

[18]

General Eric Wickberg, “Movements for Reform” (Address

at the 1971 International Conference of Leaders)

Minutes, 9.

[21]

Email in my possession.

[22]

Servants Together

(2002), 121.

[23]

A letter to Territorial and Command leaders from the

Chief of the Staff, dated 31 July 2008, stated, “…it

is the General’s wish that all copies of the previous

edition be removed from trade department shelves,

training college libraries and any other resource

centres where copies may reside, and destroyed. Also,

in publicizing the revised edition within your

territory/command, please encourage your officers and

soldiers to purchase this latest

edition and to

discard any copies they may have of the 2002 edition.”

Upon being asked about this, Commissioner Dunster

wrote further that “The General’s request for copies

of the first edition to be discarded is simply a

matter of practicality and good sense. We do not

really want classes of cadets - or others - where some

are using the old book and others the new one. That

would lead to unnecessary confusion.”

Letter to Major Kingsley Sampson, dated 19 August

2008.

[24]

Servants Together

(2002), 121.

[25]

Hans-Ruedi Weber,

Power, Focus

for a Biblical Theology (Geneva: World Council of

Churches, 1989) 167.

|